ESA - European Space Agency patch.

24 April 2018

Satellites orbiting Earth are moving at many kilometres per second – so what happens when their paths cross? Satellite collisions are rare, and their consequences poorly understood, so a new project seeks to simulate them, for better forecasting of future space debris.

Only four such collisions have taken place in the history of spaceflight so far – the majority of space debris stems from explosions of leftover propellant tanks or batteries – but they are projected to grow more common.

Satellite collisions create debris

“We want to understand what happens when two satellites collide,” explains ESA structural engineer Tiziana Cardone, overseeing the project.

“Up until now a lot of assumptions have been made about how the very high collision energy would dissipate, but we don’t have a solid understanding of the physics involved.

“We want to be able to visualise in detail how the satellites would break up, and how many pieces of debris would be produced, to improve the quality of our models and predictions.”

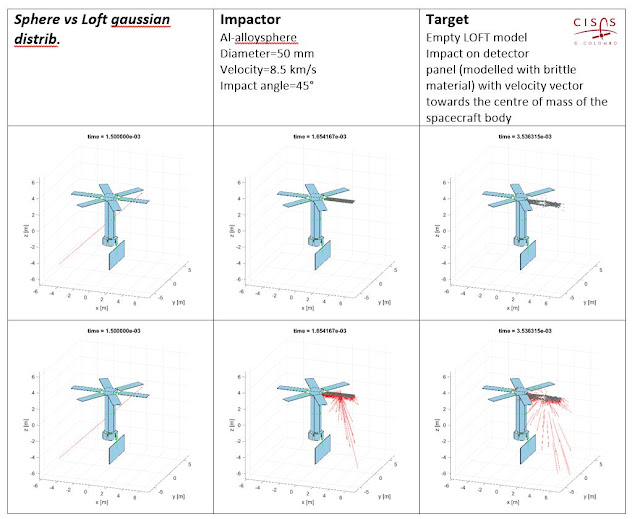

Simulated satellite strike

The total energy involved is orders of magnitudes higher than typical structural engineering for space, which focuses on enduring the violence of launch. “This is really unknown territory,” adds Tiziana.

“We need to have this understanding because we are currently working on expensive debris mitigation strategies based on our understanding of debris behaviour,” explains Holger Krag of ESA’s Space Debris Office. “We’re projecting the evolution of the debris environment up to 200 years ahead.

“Of the four known collisions, only one of them took place in the way we expected, with both satellites breaking up catastrophically, generating clouds of debris. The others were quite different, so there’s something missing from our picture.

Simulated debris strike

“By running many different collision variants then we hope to understand what happened across the actual collisions, to help substantiate our modelling.”

Two different kinds of software simulations are being undertaken: at Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute for High-Speed Dynamics and the other at a consortium led by the Center for Studies and Activities for Space at the University of Padua in Italy.

The first approach is based on a sophisticated numerical method to simulate the deformation and fragmentation processes in a collision. The colliding objects are modelled with realistic structural and mechanical properties, represented by a ‘finite element mesh’.

Impacting a hollow cylinder

These elements are converted into discrete particles as the satellites fragment. This allows the simulation of the satellites’ structural response to the collision as well as the generation of the fragment cloud, and its evolution over time.

The second approach treats the spacecraft as made up of larger elements, such as panels, payload, propellant tanks or solar arrays, attached together with physical links. When the energy transfer of the collision takes place, these links are broken apart and the elements are fragmented. A library of previous simulations and empirical data is applied to show how these elements fragment under the force of the impact.

Simulated debris impact

The two types of simulation together – operating at material and component levels – should give new insight into the underlying physics of collisions, but has begun by mimicking the effects of a single item of debris – the kind of collision that can be simulated physically in terrestrial labs.

Real-life impact test

Once these simulations duplicate the observed reality, then they will be used to reproduce entire impacts of 500 kg-scale satellites.

Clean Space: the challenge of space debris

The first known collision took place in 1991, when Russia’s Cosmos 1934 was struck by a piece of Cosmos 926. Then, in 1996, France’s Cerise satellite was hit by a fragment of an Ariane 4 rocket. In 2005 a US upper stage was hit by a fragment of a Chinese rocket’s third stage. In 2009 an Iridium satellite collided with Russia’s Cosmos-2251.

Related links:

Space Debris Office: http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Operations/Space_Debris

Fraunhofer Ernst Mach Institute: http://www.emi.fraunhofer.de/EN/index.asp

CISAS - Center for Studies and Activities for Space: http://cisas.unipd.it/

Images, Video, Text, Credits: ESA/ID&Sense/ONiRiXEL, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO/Fraunhofer Institute for High-Speed Dynamics/ESA/Center for Studies and Activities for Space.

Greetings, Orbiter.ch